The 100th Kentucky Derby

50 Years Ago, and Who’s Counting? Everybody Who Was There!

Written by Bill Doolittle Photography Courtesy of Churchill Downs Racetrack, Kentucky Derby Museum, Cathy Shircliff and Patti Speelman

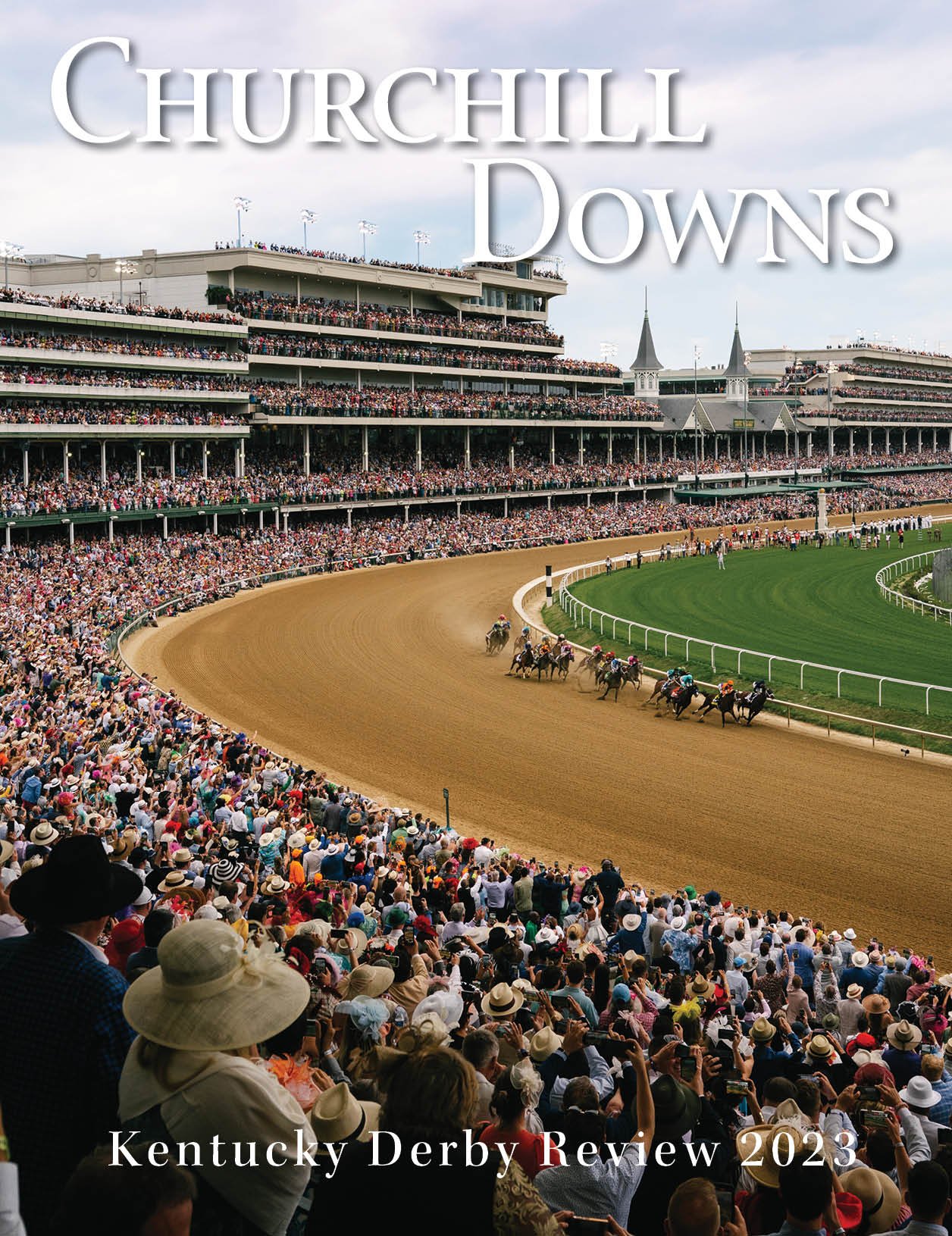

Nobody had a better view of the 100th Derby than Cannonade.

For one moment, the mahogany bay colt ridden by Angel Cordero Jr. had the entire panorama of Churchill Downs and the one hundredth running of the Kentucky Derby in front of him. All of it.

Firing between horses to burst suddenly into the lead at the top of the stretch, Cannonade could see everything: To his left, an estimated 90,000 fans packed into the Infield. To his right, 70,000 more stacked to the rafters beneath the Twin Spires – all wildly screaming. And ahead – a clear path to glory. A wide open 80-feet wide dirt racetrack. No people, no horses, not a feather in his path. A quarter of a mile straight ahead to the finish line of the 100th Kentucky Derby.

If all went right.

Trainer Woody Stephens, a sage bird if there ever was one, knew his horse was a little spooky. In his last race, the Stepping Stone Purse a week before at Churchill Downs, Cannonade had gotten “hot” before the start — — then cooled to come from well back to mow down 12 rivals. Stephens believed that seven-furlong (seven eighths of a mile) prep race had set the colt up perfectly, condition-wise, for the 10-furlong Derby. But the trainer had to wonder how Cannonade would handle what was shaping up as the largest Kentucky Derby crowd in history. A record 23 horses, and a record crowd at the time of 163,628 fans.

Many a good horse has lost the Derby mentally, before ever running a step. Others have been fine till the first turn, when it always gets tight. Or in the final quarter mile when a tremendous wall of noise hits them straight in the face. Just a moment’s hesitation, anyplace, can spell the difference between a horse that’s good enough to be in the Derby and one great enough to win it.

In the paddock, Stephens had pulled “blinkers” onto his horse’s face, little round cups outside the horse’s his eyes to limit his vision – an ancient trainer’s tool to focus a horse’s attention straight ahead, rather than on the distractions it might run by.

Stephens was still worried about the crowd and his only pre-race instructions to Cordero were for the rider to warm Cannonade up all the way down the backstretch, farther than the other jocks would normally go.

“Remember the Stepping Stone, when he acted funny about people?” said Stephens. “Warm him up way down the backstretch. Let him look at them.”

Cordero said Cannonade relaxed nicely. “He seemed to like all the people. Liked looking at them.”

At the starting gate, things were close.

Some of the Infield revelers had knocked down sections of a chain link fence designed to create a little greensward buffer between people and racetrack. Today there’s a turf track between fans and the main track. But on this day, hundreds had come over the fence and run up to the inside rail.

Starting his first Kentucky Derby, starter Tom Wagoner addressed the crowd from his stand at the gate. He told them to keep their hands down. “Don’t reach over the rail,” he said. “Let the horses have room.” And they did.

Cannonade had a disadvantageous No. 2 post position, with only one horse between him and the inside rail – and 21 outside him. That might sound good, but if a horse misses the break, gets off a bit slowly, the entire field can come over in front of him, shunting the horse back to last.

Another problem is it took more than three minutes to load the huge field. All that time Cannonade was standing in the starting gate, keyed up, ready to go. Another chance for a high-strung horse to melt down.

Conversely, a cramped and contentious start could afford a well-mannered thoroughbred the opportunity to show his class. Act the part. Stand steady and ready. Then – finally! – when the bell rings and the gates bang open, break straight and sharp. Which Cannonade did.

He did not wilt, did not shy, did not act up. Just took the tension and got ready to Run for the Roses. At last, with all 23 in the gate, Wagoner sent them away — with the vast throng yelling, “They’re Off!”

A minute and a half later, Cannonade would arrive back at this very spot – the starting gates rolled away – on top, turning for home in the Kentucky Derby, with a chance to write his name into history.

All up to him.

A Wishbone Derby

Derby Day began early for 15-year-old Mark O. Board.

“My aunt had a corner lot on Dearcy Avenue near Churchill Downs, and in those days I parked cars,” recalled Board. “I was parking cars for $10 on her lot, making sure nobody got blocked in and I got to keep the money. Then I’d go to the races.”

“That year, 1974, I remember there was a gentleman from Orlando, Florida, and he had all these stickers on his windshield. He said, ‘I don’t want to be blocked in because I’m meeting Mickey Mouse inside and we might have to leave quickly.’ ”

Of course. Why wouldn’t Mickey Mouse be at the Kentucky Derby? Everybody else was.

“My mom had driven me in the morning, and we’d stopped at the Wishbone restaurant, right across from Butler High School, my school. So I had a box of chicken for the day and when I got done parking the cars, I went to the races. I bought a general admission ticket and went in and found a spot around the first turn past the end of the grandstand. Up against the Clubhouse turn fence, with a box of chicken in my lap. That was my first Derby, the 100th, and this year I will be at my 50th-straight. After we got married, my wife Tammy and I have always gone, and she’s got a streak up to I think 26-straight now.”

But not on the first turn fence.

“I remember looking over at the box seats and the Clubhouse, and thinking, ‘Now, what can I do to get over there?”

They Call Him the Streaker

Derby Day began early for 15-year-old Mark O. Board.

“My aunt had a corner lot on Dearcy Avenue near Churchill Downs, and in those days I parked cars,” recalled Board. “I was parking cars for $10 on her lot, making sure nobody got blocked in and I got to keep the money. Then I’d go to the races.”

“That year, 1974, I remember there was a gentleman from Orlando, Florida, and he had all these stickers on his windshield. He said, ‘I don’t want to be blocked in because I’m meeting Mickey Mouse inside and we might have to leave quickly.’ ”

Of course. Why wouldn’t Mickey Mouse be at the Kentucky Derby? Everybody else was.

“My mom had driven me in the morning, and we’d stopped at the Wishbone restaurant, right across from Butler High School, my school. So I had a box of chicken for the day and when I got done parking the cars, I went to the races. I bought a general admission ticket and went in and found a spot around the first turn past the end of the grandstand. Up against the Clubhouse turn fence, with a box of chicken in my lap. That was my first Derby, the 100th, and this year I will be at my 50th-straight. After we got married, my wife Tammy and I have always gone, and she’s got a streak up to I think 26-straight now.”

But not on the first turn fence.

“I remember looking over at the box seats and the Clubhouse, and thinking, ‘Now, what can I do to get over there?”

Hearing the Horses

Over in the Infield, Donnie Whitaker spotted the Streaker.

“Everybody was saying, ‘Look at that naked guy shinnying up the flagpole,” recalled Whitaker. “I do remember him slowing down, like you said, and I was thinking he was enjoying the show. But all these years later, I’d be kind of curious, Googling up what the temperature was on that day – it was beautiful and sunny – and I’m thinking it might have been a little, um, warm on that steel flagpole. Like that little kid in A Christmas Story, sticking his tongue on a freezing flagpole. Only just the opposite effect this time. Oh, golly man, I tell you what. Youch!”

But what Whitaker remembers best about the 100th Derby is hearing the horses.

“When the Derby came on, basically what we saw was some horses and jockey heads go by, but I heard the noise. Bdrrrrrump, bhrrrr-rump. You could really hear them flying by with those hooves hitting the ground.

“So when the horses went by the first time, my buddy Robert says, ‘Why don’t you jump up on my shoulders and see if you can see it?’ When they came back around and down the stretch, I got to see a little bit more of their heads, but I heard them again, like before. Those horses, Bddddddd-rummmppp. It was an experience, and a spectacle, and a lot of fun. It was the hundredth running – and I got my eyes full as a 17-year-old young man … Yeah!”

Whitaker also remembers betting a horse earlier in the day that won. “His name was Never Bold, I think, and he won.” He also had Derby winner Cannonade – in a kind of “two-for-one deal.”

“My Derby horse was, Judger, I just kind of liked his name,” said Whitaker, who not far from the Downs. Like most South Enders he knew a little about betting the horses. Not much, but something. “I just knew I liked Judger, and I understood that he was a in double entry. You got Judger, but you also got Cannonade, and he won.”

(The two horses were coupled as a betting “entry” because both were trained by Woody Stephens.)

But Whitaker didn’t cash his ticket. He did cash his bet on Never Bold earlier in the day, but not on Cannonade.

“It was the 100th Derby. I took my ticket home and had my mom put it in her jewelry box, as a souvenir.”

A winning $2 ticket paid $5 to win, and thousands and thousands of Derby goers had it. Unlike most pari-mutuel tickets, which generally expire after a year, Churchill Downs honors all winning Kentucky Derby bets, forever. Could be cashed today. Mail it in and they’ll send you a check for $5. But no thanks, said Donnie Whitaker.

Of course, if you happened to have an uncashed ticket on Donerail, the 1913 winner that paid $184.90, that might be different. Or, you could donate it to the Kentucky Derby Museum (they don’t have one), and take at least a $184.90 charitable deduction off your income tax.

That’s if you have one.

A Radio Flyer and a Racing Form

Friends Jim Shircliff and Jimmy Rogers were already experienced Kentucky Derby Infielders and had perfected their method of bringing refreshments into the Infield.

For Secretariat’s Derby the year before, the buddies had iced a big metal cooler in the usual manner: beer on the bottom, with a layer of Coca-Colas on top to “fool” the guards at the gate. Of course, nobody was much fooled. In an era when you could bring coolers into the track people were certainly going to figure out how to smuggle in their favorite libations. You just didn’t want to be swigging on a bottle of Old Rosebud when you arrived at the gate. Gate 1 at Churchill Downs wasn’t exactly the Berlin Wall, but there was a rule.

“Our problem was that metal cooler, packed to the top, weighed a ton. We had to carry it blocks and blocks,” recalled Shircliff. “So, for the 100th Jimmy bought a little red rusted Radio Flyer wagon for $5 wagon to haul the cooler. We found a parking spot on one of the side streets and wheeled the Radio Flyer right up to the track – and in – with ease.”

Past the gate and through the tunnel under the track to the Infield, Shircliff, Rogers and Rogers’ girlfriend, Vicky Dobson, found a perfect campsite.

“We commandeered a Dempster Dumpster and we’d brought some clothesline along to rope off our territory,” said Shircliff. “That worked great until time for the Derby when everyone surged toward the track and our camp got overrun. But it didn’t matter.”

The Infield for the 100th Derby was just like the Infield of other Derbys – except more. More people, more blue jean skirts, more scanty tops, more bareback college guys.

And more sunshine. May 4, 1974, the sky came up blue and the sun shone bright on the 100th Derby.

Shircliff says he put his time to good use in the Infield, studying for the future.

“I think it might have been the 100th I learned to read the Daily Racing Form,” says Shircliff. “There’s so much time between races. I bought a Form, which had a page that explained all the little facts and tiny symbols and what everything meant. Then I applied that to the ‘past performances’ of the horses in the races – and learned a little – just a little – of how it all worked. I’ve been fascinated with handicapping ever since.”

Now a successful investment analyst and avid horse owner, Shircliff says beating the stock market is child’s play compared to picking Derby winners. (Naw, he didn’t say that. But it is.)

The British Invasion

Then Princess Margaret arrived.

The Princess was the fun-loving younger sister of Queen Elizabeth II. In London, the tabloid press followed Meg and Tony, as they called Margaret and her handsome husband Tony Snowdon, from dancing in West End clubs, to shopping on Carnaby Street with the Beatles, to attendance at the races at Royal Ascot. The Queen Mother owned a top stable, as did Queen Elizabeth – and the Windsors were prominent on the British turf.

American writer James Brough, partnering with Stephens in the book “Guess I’m Lucky,” described the scene at Churchill Downs.

“Just after two o’clock, a red carpet was rolled out across the dust of the track, ready for the number one guest, Princess Margaret and her husband at the time, Lord Snowdon. They walked between two lines of Kentucky National Guardsmen to take their seats at the top of the pagoda in the Infield at the finish line. It was easy to spot her in a little hat and dress splashed in the colors of a rainbow. The kids in the crowd hoisted a sign: ‘Hey, Meg – Had Any Winners Lately?’ “

Later, the Princess, understanding that the sun never sets on the British Empire, said she’d thoroughly enjoyed the100th Kentucky Derby. “A lovely day of racing in the county.”

Devil’s Red and Blue

Meanwhile, up in their seats, the Speelmans were getting down to Derby business.

J. Murray Speelman, the dad, had attended his first Kentucky Derby in 1929 and the whole thing captured his imagination. When newly engaged, J. Murray brought Ruth to the Derby in 1946 and when the couple married, they spent their 1947 honeymoon in Louisville for the 73rd Kentucky Derby. World War II was just over and a lot of horse names reflected that. Assault won in 1946 for the 72nd Derby for the King Ranch and Jet Pilot flew to victory in ’47 for Elizabeth Arden’s Maine Chance Farm. Calumet took it the next two years with Citation and Ponder.

“The farm that captured my dad’s heart was Calumet,” said Patti Speelman. “We grew up on Devil’s Red and Blue.” Which worked out well, with Calumet capturing eight Kentucky Derbys.

“We took a vacation somewhere every year, but most of our vacations were in cities,” said Patti. “We were not a camping family. We stayed in cities so my dad could go to the racetrack and we all went with him, and mom could go to museums and we all went with her.”

And they never missed the Kentucky Derby.

Dad and mom gone now, but the Speelman girls carry on and will be at Churchill Downs for the 150th Kentucky Derby.

A Flash of Red

The 100th was my first Derby out of the Infield.

My friend Sally Sanders invited me to join her and brothers Hal and Henry in an extra box their mom and dad had on the First Floor – out in the sunshine and right on the rail. I donned a madras tie.

The track curves around there, past the finish line and into the first turn. We had a view not just of the track in front of us, but straight up the track. So for the Derby, I could see all the way to the top of the stretch when the first horses popped out from behind the Infield wall of humanity and turned for home.

And I saw him!

Just a flash of red. And I didn’t know who it was. But I could see one horse burst to the lead, then come straight at us. Way up there a quarter mile away. There were no big video screens then, of course, but the tote board flashed up the first four leaders during the race. The numbers changed – with No. 1 – from nowhere – now on top.

I knew that wasn’t Judger – I’d tabbed his colors before the race as the favorite. I quickly checked the program – handily small in those days – to see the other No. 1 horse had red silks. Cannonade.

Down the stretch he came — out from the fence. Under the wire (there was still a finish line wire in those days), Cordero popped up in the stirrups – and just seconds later horse and rider flashed by us in bright red silks with gold bars and hoofbeats you could hear. Hudson County was second. Later I realized I couldn’t have seen the Cordero’s silks at the top of the stretch because he was crouched behind Cannonade’s head and neck. It was those red blinkers on Cannonade’s face.

Thank you, Sally!

Just a few feet away, unknown to each other then, but also on that first turn, was Mark O. Board and he was also enthralled.

“I really don’t remember seeing anything, except the ‘gallop out,’ and saw the winner then.” he said. “But I do remember hearing track announcer Chic Anderson calling the race, calling ‘Cannonade!’ all the way down the stretch. He’s still one of my favorite announcers.

“It was my first Kentucky Derby, and it was the 100th,” said Board. “A beautiful sunshiny day, and I was there.”

His People

While Jim Shircliff was mastering the Daily Racing Form, I was beginning to pay attention to the bloodlines of thoroughbreds – especially Derby winners. And Cannonade was a lesson in himself.

Bred in Kentucky by John R. Gaines, who later founded the Breeders’ Cup, Cannonade’s pedigree held everything. He was a son of Bold Bidder, from the fast, and then-dominant Nasrullah/Bold Ruler sire line that’s still cooking today. But it was his maternal side that was most interesting. His dam was Queen Sucree, a daughter of Italian-bred Ribot, who twice won the Prix de la Arc de Triumph, in Paris, and was undefeated. Queen Sucree’s dam was Cosmah and if you were starting your farm with just one broodmare, Cosmah could be it. (Dosage Profile: 9-14-14-3-4, while you are yawning.)

After the race Stephens called winning owner John M. Olin, who was grounded at home in St. Louis with a mild coronary. Olin, the principal owner of the Olin-Mathieson chemical corporation and a longtime thoroughbred horse owner, had deputized his step-daughter Mrs. Eugene Williams to stand in for him at Churchill Downs. But he’d seen the race on TV.

“It was unbelievable,” the 81-year-old owner told his trainer. “Like the feller said on his tombstone, ‘I expected this, but not so soon.’ ”

Scotch and Champagne with the Princess

In the Directors Room, Stephens and his wife Lucille sipped champagne, with Woody quickly shifting to Scotch. Churchill president Lynn Stone steered Princess Margaret to the winning trainer.

“Princess, have I introduced you to Woody Stephens?”

Meg smiled. “Oh, Mr. Stephens and I met on the stand.”

Woodford Cefis Stephens had come a long way from growing up on a small farm in Stanton, Kentucky. He started his first horse in the Kentucky Derby in 1949, ran third with Blue Man in 1952 and second with Never Bend in 1963. He won three Kentucky Oaks and five-straight Belmont Stakes. He had trained for Capt. Harry F. Guggenheim, of the New York museum Guggenheims and won his second Kentucky Derby in 1984 with Swale, for Claiborne Farm.

“One reason I developed a liking for horses early on,” Woody explained in Guess I’m Lucky, “might have been the fact that when my dad hoisted me up on one of them, or on the back of one of them, I was five or six feet higher off the ground, looking down at people instead of up. I got that boost up in the world from him, starting when I was three or four years old. He let me ride them as they pulled the hitch that did the plowing. It provided a lot more pleasure, I found out later, than hoeing tobacco for fifty cents a day. Dad used to say, ‘Woody’s a born horseman,’ and I was happy to hear it, because I didn’t want to be considered a born field hand.”

It was also the first Kentucky Derby victory for Angel Cordero Jr. The son of a jockey in Puerto Rico, Cordero was the leading rider at Saratoga 14 times and in his career, won 7,057 races, including the Kentucky Derby three times. Cordero was tremendously popular with fans, who loved his smiling, happy temperament – but ruthless on the track. Columnist Joe Hirsch quipped that, “Angel checked his halo at the jock’s room.”

“When you decide you are going to be a jockey,” Cordero told Sports Illustrated’s Whitney Tower, “you know that eventually you’ll get to ride your first race. Then you hope that someday you’ll get your first winner. But the Kentucky Derby – that’s something you only dream about.”

On the Sunday morning after the 100th Derby, Stephens was out on the track on his stable horse, as usual, chatting over the fence with reporters. They wanted racing details, but the winning trainer was still soaking it all in.

“Imagine that,” said Woody, “A poor boy from Kentucky up on that stand with the Princess of England.”